Robots fly, walk, swim and crawl with new sensors and artificial intelligence to spot—and sometimes fix—problems

A growing cadre of tech companies are stepping up to address a massive problem hiding in plain sight: the aging of trillions of dollars’ worth of bridges, tunnels and factories across the U.S.

Our nation’s most critical infrastructure—from pipelines and industrial plants to ships and suspension bridges—is slowly going to pieces, leading the American Society for Civil Engineers to give our infrastructure a C-minus on its most recent report card.

The reasons are various. Our planet is blanketed in a pitiless mixture of liquids and gases that are forever trying to disassemble us, and everything we build, at the atomic level. Oxygen keeps us alive, but it’s also highly reactive, an eager partner for metals and most everything else we build from. Rust happens. Protective coatings oxidize. Things catch fire.

On top of that, waves, wind and the expansion and contraction that comes with the seasons erode and crack steel and concrete. This can have devastating consequences, as when a condo building collapsed in Surfside, Fla., and when a bridge buckled in Pittsburgh, just hours before President Biden was scheduled to deliver a speech in the city about the state of the country’s infrastructure.

Florida’s Champlain Towers South deteriorated over decades before collapsing in 2021 in one of the deadliest building failures in U.S. history. Photo: Amy Beth Bennett/Sun-Sentinel/Zuma Press

Pipes, containment vessels, I-beams, and moving parts all fail and, eventually, return to the elemental state from which they came. Climate change and the increasing number of extreme weather events are accelerating the process.

Perhaps the biggest challenge, as Kurt Vonnegut once wrote, is that “everybody wants to build and nobody wants to do maintenance.”

Call in the robots

On the east bank of the Mississippi River, 20 miles southeast of Baton Rouge, La., Shell USA has operated the Geismar chemical-manufacturing plant since 1967. There, the company makes industrial chemicals that go into things including synthetic fabrics, detergents and plastic containers.

Until very recently, when Shell needed to inspect parts of the aging plant, it had to shut down the affected section completely. Then the company would bring in workers who had to risk life and limb to scale parts of the enormous plant to check every inch of it.

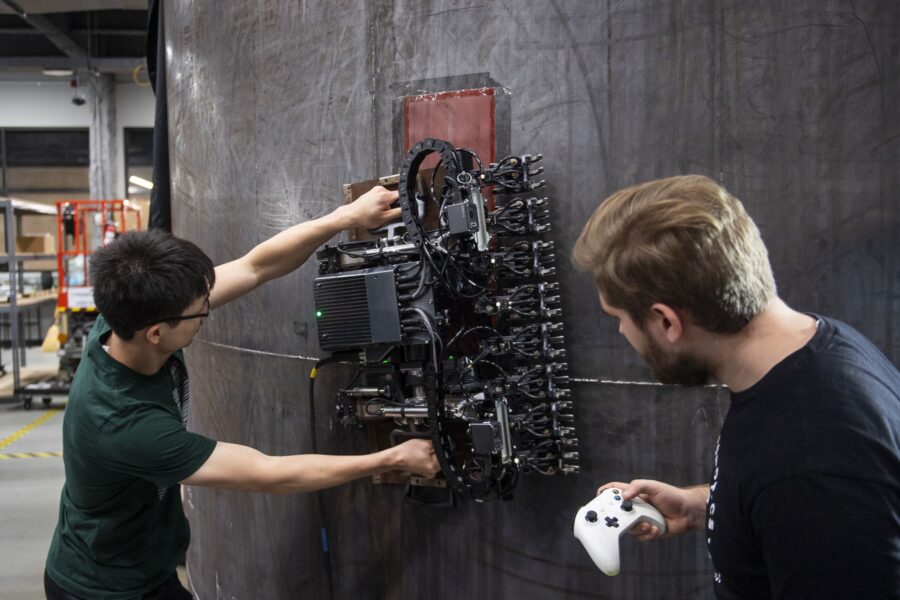

These days, Shell is able to keep the plant running, and keep repair personnel on the ground and at a safe distance as they operate wall-climbing robots that inspect things like steel holding tanks at millimeter resolution, says Steven Treviño, a robotics engineer at Shell. Using a variety of sensors, the robots can look for both corrosion and cracking. This helps the team shorten the list of things they have to take care of when a full shutdown occurs.

The magnetic wall climbers Shell is using are made by a Pittsburgh-based startup called, appropriately, Gecko Robotics. After testing the Gecko robots at Geismar, Shell plans to expand their use to offshore facilities.

The TOKA 5 robot from Gecko Robotics, a Pittsburgh-based startup, allows workers to conduct inspections without risking life and limb. Photo: Nate Smallwood for The Wall Street Journal

“Think of us as the doctors for our sites and for our equipment,” Treviño says of his team of inspection and maintenance techs. “Like a doctor, we non-destructively test the patient, and determine what are the next steps—do we do nothing, or do we prescribe something?”

Shell’s approach to keeping this corner of its vast infrastructure operating exemplifies a broader trend across maintenance of military and civil infrastructure of every kind. The entire inspection and maintenance industry is transitioning—gradually, and sometimes begrudgingly—from performing maintenance on a set schedule, to using a new suite of tools to figure out what needs fixing before it breaks, says Adam Middleton, a managing director at Siemens Energy.

Those tools include robots that fly, walk, swim and crawl, new types of sensors, and artificial intelligence to digest the data they gather and make predictions based on it, says Treviño.

“I think one of the fascinating things is how much of the infrastructure our world runs on is untouched by digital technology,” says Adam Bry, chief executive officer of Skydio, a San Mateo, Calif.-based drone company.

Skydio recently shut down its consumer drone business to focus exclusively on enterprise customers. These customers include more than 80 utilities, transportation agencies in 35 states, and oil and gas firms—including Shell USA. All use its drones to perform regular inspections of portions of their critical infrastructure, from substations and power lines to bridges and factories.

For drones, these kinds of inspections are all about using the same cameras that appear in our cellphones to automate visual inspections. Images can be fed to a machine-learning system—also known as artificial intelligence—which has been trained to look for damage.

As the nation’s pipes and treatment plants age, water-main breaks and boil-water advisories are becoming increasingly common. WSJ explains how decades of disinvestment brought the country’s water infrastructure to a tipping point. Photo illustration: Ryan Trefes

At the same time, these drones are able to precisely map the surface of objects in three dimensions. This yields a hyper-realistic model that can be virtually “inspected” by humans from the comfort of an office, while also being fed through AI that flags anything suspicious.

Treviño calls the shift that’s under way a move from time-based to risk-based inspections. Bry calls it a move toward condition-based maintenance. However you describe it, “it’s knowing the condition of the asset rather than doing it on a timed schedule,” he adds.

Nature is a harsh mistress

Unlike fintech, proptech and all the other buzzy “-tech” subgenres, “maintenance tech” isn’t a neologism anyone is trying to make happen, yet. Perhaps they should, given how important it is for our everyday lives.

Over the past 50 years, a number of studies of the direct costs of corrosion have been conducted. The most recent was in 2013, but these studies always come up with the same figure—between 3% and 4% of GDP. Other studies have estimated that, when you add in indirect costs, the total is roughly double that. Globally, that means corrosion is costing humanity trillions of dollars a year.

“There are hundreds of types of corrosion,” says Jake Loosararian, CEO of Gecko Robotics, “and we’ve been developing technology and software to analyze what kind of damage is happening.” Gecko began as a robotics company, but has since expanded into creating software to process the data its robots gather. The startup makes systems that are now used to track more than 60,000 assets across the globe, including power plants, pipelines, oil refineries, dams, U.S. Navy vessels and other military equipment.

A Skydio drone inspects a bridge. The company recently shut down its consumer drone business to focus exclusively on enterprise customers. Video: Skydio

All creatures great and, increasingly, small

When it comes to inspections, “often the data you need is literally in plain sight, it’s just hard to collect it,” says Bry, of Skydio.

Collecting that data is falling, increasingly, to things that crawl, fly and swim.

There’s Gecko Robotics’ magnetized, wall-hugging crawlers, and Skydio’s compact, autonomous, go-anywhere drones. Underwater, a similar evolution in robotics has been happening—only the environment is in some ways far more challenging.

VideoRay has been building underwater robots for more than 20 years, says Brad Clause, an executive at VideoRay.

In the aquatic environment, there is no GPS, and satellite communications are impossible. So it’s taken decades of research—some of it funded by the U.S. Navy, but most of it subsidized by the biggest customer for remote vehicles, which is the offshore oil industry—to replace all of these technologies with equivalents that work underwater.

For navigation, there’s acoustic positioning relative to surface transponders. For communications, acoustic modems. For sensing cracks and corrosion, remote vehicles are able to use cameras and ultrasonic thickness sensors—but only if the robots are powerful enough to resist powerful currents, and precise enough in their navigation to get in close. Underwater, corrosion happens at a pace that makes terrestrial environments seem tame—where on land, inspectors are concerned if paint seems to be compromised, in the water, they are looking at the thickness of structures to determine how fast they’re dissolving.

VideoRay’s latest generation of remote vehicles weigh 38 pounds and can be carried by one person. That way, it can be delivered anywhere, quickly, without a large support crew, crane and the kinds of ships once required by older robots, which could weigh several tons.

Similarly, Skydio’s drones are tiny—weighing less than 3 pounds, and less than two feet wide. Their size is critical to allowing them to fly nimbly both indoors and out, aiming their cameras at the structures they’re inspecting.

“We are the first mile of digitization,” says Bry of Skydio. “Drones turn out to be an incredibly powerful tool to do this because they can literally go almost everywhere.”

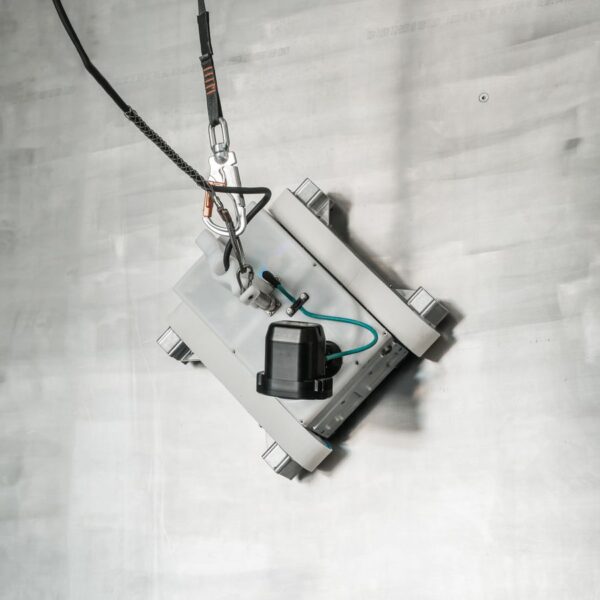

The Anybotics four-legged robot can carry cameras, thermal sensors, and an electronic ‘nose’ when performing autonomous inspections in industrial facilities. Invert Robotics’ inspection robots can climb non-magnetic surfaces using suction. Anybotics; Invert Robotics

On the ground, robots like Zurich-based Anybotics’ four-legged ANYmal derive their utility from being about the size of a medium-size dog, and able to go where humans go—including up and down stairs. Using cameras, lasers, thermal sensors and even electronic “noses,” they can automate the inspection of industrial facilities.

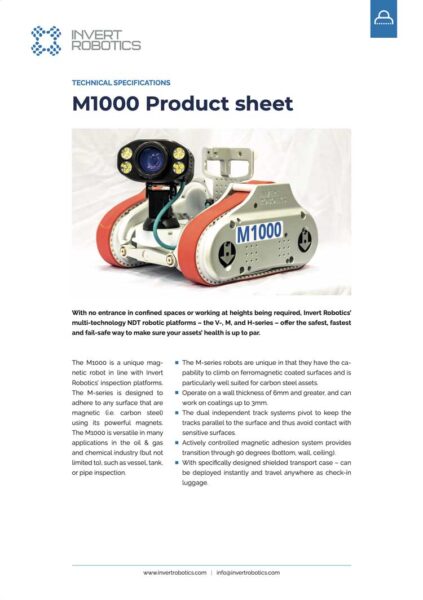

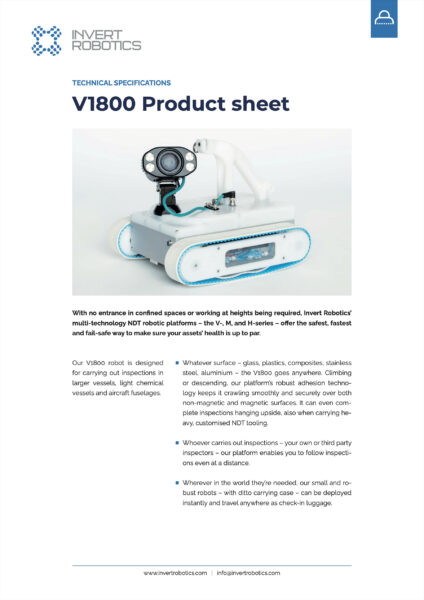

And then there’s Invert Robotics, which created a robot that weighs less than 11 pounds, is the size of a large briefcase, and can stick to nearly any smooth surface using tiny suction cups, almost like those on the arms of an octopus. The result is a robot that can drive all over the insides of reaction tanks in pharmaceutical factories, the outside of an airplane, and more, to do minute inspections for corrosion, and chemical and biological contamination.

Rosie the robot riveter

Once a problem has been assessed, robots can also, increasingly, take on the roles humans once had in fixing it.

Greensea makes underwater robots that scrub the bottoms of ships, to prevent the buildup of barnacles, tube worms and other gunk—known as fouling—which can force them to use 20% more fuel to get where they’re going. Typically, cleaning a ship requires a group of human divers—or if it’s in particularly bad shape, dry dock.

Greensea’s hull-scrubbing robots can be operated by crew members onboard a ship. Photo: Greensea

Greensea doesn’t sell these robots; instead, it offers a subscription service that guarantees a clean hull for customers, who can either elect to take the robots with them onboard their ships, or have them cleaned when they put into a port, says Greensea chief executive Ben Kinnaman.

Greensea also illustrates the way an overlapping ecosystem of companies has developed around using robots to do inspections, and software to process what they find. In addition to its hull-scrubbing robot, the company makes the Opensea software platform, which it began developing in 2006. Opensea software is what runs VideoRay’s underwater vehicles, and can also be found on vehicles of several dozen other manufacturers, says Kinnaman.

The waiting is the hardest part

Let’s say you’re an energy company for which outages can add up to billions of dollars a year in lost revenue and additional costs. In that case, updating your systems for inspection and maintenance can pay for itself very quickly indeed, says Middleton, of Siemens Energy.

The problem, however, is that companies, governments and militaries with vast infrastructures already have systems for maintaining them. And those systems are dependent on people who are used to doing things a certain way.

“I will be honest, the biggest barrier to adoption of this kind of technology is probably human,” says Middleton. “If people feel for example that this is impinging on their expertise, it’s going to be potentially difficult to get them to understand and appreciate.”

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com

Appeared in the August 19, 2023, print edition as ‘The Robots Keeping Bridges From Collapse’.

Source: The Wall Street Journal